This article is for the use of the members of the Society for Creative Anachronism. The author gives his permission for it to be reprinted or to be put on web sites by members for their use, as long as proper credit is given to the author.

John R Edgerton (AKA Sir Jon FitzRauf) Newark, California

January. 2016

Copyright 2016 by John R. Edgerton. All rights reserved.

First published in the Fall 2016 issue of Quivers and Quarrels, the official SCA archery E-newsletter.

This is not an official publication of either The Society for Creative Anachronism or the Kingdom of the West.

This article is not published by the Society for Creative Anachronism Inc.

Since the information contained herein may be used under circumstances outside of their control, neither the author nor the Society for Creative Anachronism Inc. assume any responsibility whatsoever for any loss or injury resulting from such use.

Preface

I was once on my computer with other archers discussing the history of archery and one of them said something to the effect of “Of course medieval nobles never used archery, they had their servants do the hunting for them.” Then most of the other archers agreed with this complete misstatement of actual history. I have even heard this misconception repeated by peers of the SCA, who should have a better knowledge of medieval history. This has often taken the form of: “In the Society we are all consider to be nobles. Nobles never used archery. Therefore archers should not be nobles.”

I then decided that I needed to provide some information to correct this absolute misunderstanding of historical fact. I think the best statement of the actual reality comes from Erik Roth in his “Hunting in the Middle Ages”.

“However, hunting was by far the most popular diversion among the nobility and indeed some of the clergy throughout the middle ages, sometimes becoming an obsession occupying every moment of free time. Some women also participated in the less strenuous and dangerous forms of hunting. Hunters rose at dawn and set out on foot and on horseback with or without dogs and with such an array of spears, swords, and daggers as well as handbows and crossbows as to make hunting seem almost another kind of warfare. In fact it was considered a means of keeping in readiness for warfare, the true function of the noble”

The intense involvement of royalty, greater and lesser nobility, gentry, clergy and even wealthy merchants is well noted in the writings and images of the time as well as in modern research.

Richard Almond, in his “Medieval Hunting”, states:

“For young men of the upper classes, the three basic accomplishments – facility of address, the practice of religion and mastery of etiquette – were acquired early in life, and were followed by knowledge of literature, music and the visual arts and competence at dancing plus training for war, hunting, archery and indoor games. From hunting children learned several essential skills, including horsemanship and the management of weapons, and gained knowledge of terrain, woodcraft and strategy.

In his love of hunting, the medieval noble usually had the example of his monarch. Famous royal hunters included Holy Roman Emperors Frederick II of Hohenstaufen and Maximilian I, Kings Edward III and Henry IV of England and Philip II of France. Royalty and the upper classes hunted as part of their heritage; it was expected of them; it was part of being a gentleman.”

In England, there is a well-documented history of the nobles using the bow in hunting from before Norman times to the sixteenth century.

“Practically every English king hunted; indeed, it was often their favorite leisure activity, and many were skilled at its various facets, including shooting with the bow. We have seen a number of kings using bows, usually crossbows, from William the Conqueror and Richard the Lionheart to Henry VIII, the latter being able to draw the longbow.” i

“There were many others who hunted legitimately too. As with kings, so with nobles and knights; most hunted, enjoyed hunting, were skill at it, and sometimes suffered accidents in the course of their sport. Abbots, bishops, and even popes were known to hunt.” ii

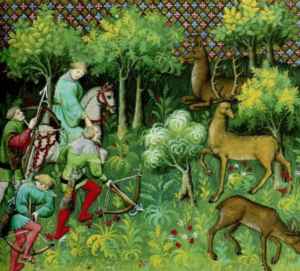

“The two basic kinds of hunting were falconry and venery, venery being further divided into the chase and the hunt. In the chase, the game was pursued, usually with dogs, it was in the hunt that bows and arrows were used. … The usual form of hunting the nobility was “bow and stable” in which archers took up fixed positions while deer were driven past them. However, some bowmen ranged forests stalking their prey and shot ‘at view’, much like some of today’s hunters.” iii

“The medieval English aristocracy loved no leisure activity more than hunting. Jousting, feasting, dancing, gaming, and polite conversation might have rounded out these activities, but none competed with the total cost, time, and effort that the aristocracy devoted to hunting. Immense swaths of countryside were legal forests, and hunting parks and lodges liberally dotted the landscape.

Literary works invoking the hunt, and the records of its laws, rights, and disputes, are extensive.” iv

“In the late middle ages it became fashionable for nobles to take part in crossbow competitions. Kings and even queens took part in competitions, and sometimes won them, sometimes even through merit. For sport, for competitions as well for hunting, the nobility and even royalty needed to practice. A sad example of this is the last record of the sons of Edward IV, the Princes in the Tower, who were seen shooting bows and playing in the Tower before they disappeared.” v

Given my known bias in favor of archery, I am basing my support of archery as being used by nobles in the hunt and sport upon the writings of known experts and period sources on the subject, rather than just my own words. I researched archery in hunting and sport and even though I can only read sources written in English, I found a vast amount of information and images on the subject. I have included some of the more interesting and pertinent in this paper.

If you are interested finding some current writings on medieval hunting, I suggest reading: “Medieval Hunting” by Richard Almond. “The Art of Medieval Hunting: The Hound and the Hawk”. Or “With a Bended Bow’ by Erik Roth.

Medieval Period

To survey a variety of primary sources in this time period, I have brought references from a variety of sources, from individuals to texts, crossing over various cultures and geographic locations for an extensive amount of time. Doing so allows us to see that the influence and spread of archery of this type is broadly based and not limited in scope or locale.

Byzantium

The earliest example I have found so far is from the Byzantine Empire in the late sixth century, when the Emperor Maurice stated in his “Strategicon” that: “We wish that every young Roman of Free condition should learn the use of the bow and should be constantly provided with that weapon.”

We then find mention of the graves of Scandinavian princes of the pre-Viking period containing both bows and hunting and war arrows. vi

Louis the Pious, a son of Charlemagne and king of Aquitaine was as an enthusiastic hunter as his father.

“Three days in each week he devoted to the administration of the law, and his sage decisions were replete with equity. Louis was bold and energetic as well as wise: no archer drew the bow with greater strength,” vii

Around the same time, King Alfred the Great of Wessex (871-899) was, according to Asser his biographer, also an outstanding archer. viii

Charlemagne

Charlemagne, King of the Franks (742-814) was also a noted hunter. He hunted till his death at the age of 72. He set up forests as his own private hunting preserves or hunting parks.

“Charlemagne was particularly found of hunting in his youth and chased deer, boar and wild oxen with javelin and ‘small bow and short or long arrows’.” ix

During this time, “Both lay and ecclesiastical aristocrats shared a passion for the chase. As soon as he began to emerge from childhood, a young man was trained to mount his horse, handle bow and boar spear, run the dogs and cast the falcons.” x

“In the eleventh to fourteenth centuries the kings of England, their households, noble and knightly households practiced archery mainly as part of their enthusiasm for hunting. Some or all of them may have practiced archery as a training sport in their childhood and youth to prepare them for the hunt.” xi

The Knightly Arts

Pertus Alfonsus (1062-1140) defined the noble curriculum for physical training when he wrote his “Septem Probitates” or the “Seven Disciplines” of the knightly arts. The third of these included archery.

“The third, that he shoots well With crossbows, arm, and hand- Bows, these he may well use Against princes and dukes.” xii

The Normans

“The chroniclers of Post-Conquest England recount several stories about the enthusiasm of William the Conqueror and his sons for hunting and their skill with the bow. One such tells of William running out of arrows while hunting and having to instruct a smith how to make arrowheads to his specification. …The real point of these stories is kings and princes of Norman England hunted with the bow, and so had a good understanding of the characteristics necessary in a bow for it to be effective.” xiii

William’s second son, William Rufus was also very fond of hunting. In 1100 while hunting in the New Forest, an arrow shot by his hunting companion killed him. Not all hunters’ experience in the forest was always quite so fatal. Hubert, (656- 727) the eldest son of Bertrand, Duke of Aquitaine, while chasing a white stag with his hounds, had a vision and a religious conversion. He later became bishop of Liege. After his death, he was declared a saint and became the patron of hunters, archers and woodsmen.

John of Salisbury a twelfth century author and bishop of Chartres commented upon the hunting of Norman nobles:

“In our time,” says the author, “hunting and hawking are esteemed the most honourable employments, and most excellent virtues, by our nobility; and they think it the height of worldly felicity to spend the whole of their time in these diversions; …” xiv

Norway

In the Heimskringla – “The Saga of Siguard the Crusader”. King Siguard of Norway (1103-1130) says: ‘

“There does not seem to be a more lordly and useful sport than to shoot well with a bow; …” xv

In the King’s Mirror, from about 1250, this was written for the education of King Magnus Lagabote of Norway. It was written:

“It is also counted rare sport and pastime to take one’s bow and go with other men to practice archery.” xvi

And in regard to combat:

“Now it seems needless to speak further about the equipment of men who fight on horseback; there are, however, other weapons which a mounted warrior may use, if he wishes; among these are the “horn bow” and the weaker crossbow, which a man can easily draw even when on horseback, and certain other weapons, too, if he should want to use them.” xvii

These noble youth were trained by knights or clerks that:

“…were expected to imbue their charges with the ideas of nobility and to teach the accomplishments that were a mark of that status. The tutors were responsible for providing a variety of educational experiences. Much of the education was tied to the military life that the elite would be expected to embrace. Training in horsemanship, archery, and the use of weapons such as lances and broadswords was essential.” xviii

Venice

“In Venice, nobles and commoners trained together with the crossbow. And from these groups of aristocrats some were recruited to serve about the merchant galleys and were know as the ‘Noble Crossbowmen’. This was often the beginning step in a career in politics or the military” xix

The Council of Ten was one of the major governing bodies of Venice.

“… the Council of Ten had stressed the importance of learning to use bow and crossbow ‘to nobles, citizens and populace alike’. Indeed, the prizes at the annual competitions for each weapon on the Lido were won with some regularity by patricians.” xx

Medieval Hunting Books

“Hunting was engaged by all classes, but by the High Middle Ages, the necessity of hunting was transformed into a stylized pastime of the aristocracy. More than a pastime, it was an important arena for social interaction, essential training for war, and a privilege and measurement of nobility” xxi

“This practical evidence of the nobility’s enthusiasm for archery is strongly supported by the two great hunting manuals of the period, Gaston Phoebus, Count of Foix’s Book of the Hunt and Edward, Duke of York’s The Master of Game. The count of Foix tells us more about the use of archery in hunting. In both books bows and arrows are mentioned in the context of ‘bow and stable’, that is, where the game is driven towards archers standing in prepared positions, and both mention all kinds of nobles, up to and including the king, taking part.” xxii

“When the royal family and the nobility were conducted to the places appointed for their reception, the master of the game, or his lieutenant, sounded three long mootes, or blasts with the horn, for the uncoupling of the hart hounds. The game was then driven from the cover, and turned by the huntsmen and the hounds so as to pass by the stands belonging to the king and queen, and such of the nobility as were permitted to have a share in the pastime; who might either shoot at them with their bows, or pursue them with the greyhounds at their pleasure. We are then informed that the game which the king, the queen, or the prince or princesses slew with their own bows, or particularly commanded to be let run, was not liable to any claim by the huntsmen or their attendants; but of all the rest that was killed they had certain parts assigned to them by the master of the game, according to the ancient custom.

This arrangement was for a royal hunting, but similar preparations were made upon like occasions for the sport of the great barons and dignified clergy.” xxiii

Training of noble youth

“His physical education began at the age of fourteen with vigorous sports and exercises, including music and dancing. One of the most important of these exercises was the chase. A good hunter had to be well trained in hawking with the falcon, riding, running, jumping, climbing, hurling stones, casting the spear, shooting with the bow, and wielding the battle-axe” xxiv

Royal archery gear

“Henry son of Edward I had two arrows bought for his use in 1274 when he was still only five, and his relative John Of Brabant had a wooden crossbow and swords for fencing fifteen years later.” xxv

“… children’s bows were a distinct commodity by 1475 when the wood for them was imported from Spain. One was bought for the five-year old Prince Arthur, son of Henry VII in 1492, and his sister Margaret shot a buck at Alnwick (Nland.) in 1503 when she was fourteen, presumably with a similar light bow.”

“Members of the royal family and the nobility used bows in their great enthusiasm for hunting. The records of the royal household for July 1334 show that Edward III paid Walter Daly 10/- compensation for having broken his bow, presumably either when shooting for sport or hunting.” xxvi

“John of Gaunt showed his taste for high grade, even flamboyant, archery equipment in 1372 when he order ’40 good arrows, with heads of good steel, and well and cleanly fletched with peacock feathers’” xxvii

“In 1390 Henry Bolingbroke bought a bow for 6/8d specifically as a gift for his father, John of Gaunt.” xxviii

“Another example of a royal archer is Edward IV, for whom ‘brode arrow hedes, shotyng gloves and sterns…’ were bought ‘…for his disport.’” xxix

Scotland

Royal archers were not confined to just England alone. To the north in Scotland…

“James I., of Scotland, who had seen and admired the dexterity of the English Archers, and who was himself an excellent Archer, endeavored to revive its exercise among his own subjects, by whom it had been much neglected, and for this purpose established the society of “The Royal Archers of Scotland,” xxx

James IV of Scotland had a bodyguard of archers that were Scottish nobles. xxxi

Poaching

Court records of the time, regarding cases of poaching show that nobility, gentry and clergy as well as commoners had a taste for the venison of the crown and others.

“Men, and some women, of all social groups hunted in medieval England. How much of their hunting was legal depended on their wealth and status: the king’s hunting was preserved by Forest Law; the wealthy had their parks but the mass of the population had very limited access to legal hunting.” xxxii

“The Forest Laws could hit knights just as hard as they would lower social groups. In 1272 Ralph le Wasteneys of Tykeshale and Philipde Barynton, lord of Creighton, went hunting with bow, arrow and greyhounds in the forest of Kinver.” xxxiii

“In 1271 a local knight, Walter de Belle Campo, accompanied by his squire, Henry of Wysham, two grooms and others of his household went hunting in Feckenham Forest. … In the following year, another knight William de Boterell with two companions entered the same forest with bows and arrows and hounds.” xxxiv

“Lord William de Valance, two of his knights, two of his sons and some foreign guests went hunting in Kinver Forest in 1276. Lord William himself killed a buck with a bow and arrow, while one of his sons shot a hind. They ended up before the King’s court, since the king was the redoubtable Edward I who had a keen interest in his forests.” xxxv

“In 1262 Ivo, Parson of Bishampton, Simon and William both sons of Robert de Monte of Grafton and other unnamed men spent three days in Feckenham Forest with bows and arrows ‘with intent to offend against the king’s venison.” xxxvi

Clearly, all of these sources demonstrate a broadly based core of activity that is well entrenched in all social classes, not only as a skill couched in hunting but as a sporting activity that was highly competitive and prized. Archery was as much a part of the social and cultural core of life as many other interests were.

Renaissance

In the Renaissance, the cultural expansion and growth of archery is even more well documented. This evolution brought about a greater amount of class mixing and social equalization. Fraternal organizations and Royally chartered groups based on the skills of archery validate the admiration of these shared skills. Royal support of such skills then is expanded to include all types of missile weapons in some cases, further validating the recognition of the skills and the individuals who practiced and perfected them. It must be noted that archery also crossed gender lines, as a sport where women could not only take part but excel at the skill and compete and beat their male counterparts.

Writings encouraging archery

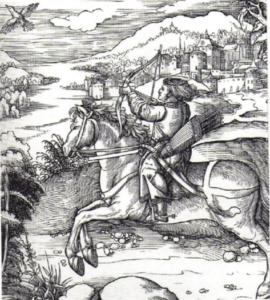

with crossbow and handbow. By Durer in 1470. (Public domain))

“Serving as tutors in the courts of rich Italian nobles, fifteenth-century humanists such as Petrus Paulus Vergerius, Guarino da Verona, Vittorino da Feltre, Leone Batista Alberti, Mapheus Vegious, and Aeneas Sylvius Piccolomini (Later Pope Pius II) not only pored over classical manuscripts but also extolled swimming, running, horseback riding, acrobatics, archery, swordplay, and wrestling.

In 1528, Baldassare Castiglione wrote in his “Book of the Courtier” that “His ideal courtier was “well built and shapely of limb.” An expert at swordplay, archery, and horsemanship, and a participant in “all bodily exercises that befit a man at court” because it called forth “the quickness and suppleness of every member.” The Courtier was quickly translated into Spanish, French, and English as a prescribed text for aristocratic manners—and physical activity—throughout Europe.” xxxvii

Sir Thomas Elyot in 1531 wrote “The Boke Named the Governour”. This was written to guide those that would be filling high positions in government.

“The long-bow is most commendable of all sports, first for its utility in national defence, archery being pre-eminently an English pursuit, and secondly as pastime and solace. It ‘appertaineth as well to princes and noblemen as to all others, by their example, which determine to pass forth their lives in virtue and honesty.’” xxxviii

In 1545 Roger Ascham wrote an entire book, “Toxiphilus” extolling archery in familiar Renaissance terms: “How honest a pastime for the mind; how wholesome an exercise for the body; not vile for great men to sustain.” xxxix

Roger Ascham “…In 1545 he presented ‘Toxophilus” to Henry VIII., who was so pleased with it that he awarded the author a pension of 10l. a year, which was confirmed by Edward VI. In 1548 he was appointed reader to Princess Elizabeth, and probably the skill of Edward VI. and Queen Elizabeth with the bow was due to his instruction. Edward VI. seems to have been fond of archery, and from entries in his diary we find that he frequently saw his guards shoot, and himself contended with his courtiers;…” xl

Even important churchmen encouraged the learning and practice of archery in their writings. Pope Pius II stated in his earlier writings in 1450:

“Every youth destined to exalted position should further be trained in military exercises. It will be your destiny to defend Christendom against the Turk. It will thus be an essential part of Your education that you be early taught the use of the bow, of the sling, and of the spear; that you drive, ride, leap and swim. These are honorable accomplishments in everyone, and therefore not unworthy of the educator’s care.” xli

The founder of the Protestant revolution, Martin Luther in the early 1500’s, also wrote.

“No spoilsport, Luther urged his followers to pursue “honorable and useful modes of exercise” such as dancing, the “knight sports” of fencing and archery, and the more physical demanding exercises of wrestling and gymnastics.” xlii

Archery Confraternities

Archery guilds or confraternities were common in Europe, particularly in Northern France, Flanders and Germany. The crossbowmen joined the Saint George guilds and the hand-bow archers joined the Saint Sebastian guilds. The more wealthy participants usually joined the crossbow guilds and the less wealthy joined the hand-bow guilds. Nobles and royalty were often found in both confraternities. A membership list for a crossbow confraternity lists some of its members under the headings of: Dukes, Counts, Knights, and nobles.

“The Saint George guild register contains the names of 28 noble members before the other 902 guild-brothers. The nobles are harder to date, as they are in a far more ornate and careful hand than the other names. A further 20 noblemen appear in the membership list among the 902 guild-brothers. Of these forty-eight noblemen, two are unidentifiable, as they are listed only by their titles, ‘my lord the captain’ and ‘my lord the president’. Five of the forty-eight can be securely identified as members of both the archers as well as the crossbowmen.

Additionally six noble men were archers, but not crossbowmen. The 54 noblemen were a diverse mix of great lords and newly ennobled patricians.” xliii

Duke Philip the Bold of Burgundy joined the Guild of Saint George in Ghent in 1369.

“The duke continued to cultivate the city’s crossbowmen after becoming a member, participating in a shooting match in Ghent two years later. In fact, as the late-fifteenth- century register of matriculation for Ghent’s crossbowmen demonstrated, all subsequent Burgundian dukes and their Habsburg successors maintained membership in the Saint George confraternity.” xliv

Philip the Good Duke of Burgundy and later King of France, as Philip III, was a member of several archery guilds.

Scotland

King James V.

“Philip the Good, as we shall see in chapter five, joined many shooting guilds. His membership in Bruges in the aftermath of rebellion can be interpreted as ducal effort to become integrated with the towns and in doing so to keep peace, even to gain support from the most powerful in civic society. Like his father, Anthony the Great Bastard of Burgundy joined many shooting guilds. Anthony was a knight of the Golden Fleece and a famous chivalric figure in his own right. He became ‘king’ of the Ghent crossbowmen and led

the Lille crossbowmen to the Tournai competition in 1455. In Bruges, he was a member of both the archers and the crossbowmen, eating with the archers at least once as the king.” xlv

“The records indicate he had a tutor from age five to thirteen but he was more inclined to learn the rules of chivalry and courtesy. He learned riding, shooting, archery and sword play and he may have learned some music, dancing, games and tales from his gentleman usher.” xlvi

Women and Archery

There is evidence that the ladies of the Renaissance also were active in various sports, including archery.

“In 1530 Lord W. Howard was sent as ambassador from England, to negotiate an interview between James V. and his uncle Henry VIII.; and the Queen-mother challenged James to produce three landed gentlemen and three yeomen to contend in archery with six of the ambassador’s suite, the prize being 100 crowns and a tun of wine; and though the Englishmen are reported to have conducted themselves as skilful and excellent archers, the Scots won. From this it is evident that at this time archery was a popular pastime among all classes. Ladies also used the bow to good purpose in the field-sports of the day, as Sir F. Leake, writing (in 1605) to the Earl of Shrewsbury, says: ‘ My right honourable good Lord, –Yo. Lordshippe hath sense me a verie greatte and fatte stagge, the well-comer being stricken by yo. right honourable Ladies handes . . . howbeit I knoe her Ladishipp takes pitie of my bucke sense the last tyme yt pleased her to take the travell, to shote att them. I am afreyde that my honorable Ladies, my Ladies Alathea and my Ladie Cavendishe wyll commanded their aroe heades to be verie sharpe: yett I charitablé trust such good Ladies wylbe pittifull.’” xlvii

“Margaret was the eldest daughter of Henry VII of England and Elizabeth of York, born on 28 November 1489 at the Palace of Westminster, a year and a half before her famous brother, Henry VIII.

Margaret Tudor’s life was in many respects as contrary and tempestuous as that of her granddaughter, Mary queen of Scots.

Margaret reveled in court life and enjoyed her position as princess to the full; she began a lifelong love affair with beautiful clothes, delighted in dancing and music as well as archery and playing cards.” xlviii

“As a result, she [Mary Queen of Scots] was popular with the common people but not the nobility; she played croquet, golfed, went for hunts and archery practice, sung, danced, and, in general, showed an admirable zest for life.” xlix

Henry VIII and family

Henry made a great showing of his skill as an archer in 1520, at the Field of the Cloth of Gold in his meeting with King Francis I of France. The target was a circle about a hand span in width and about 240 yards away.

“And right well did Henry, on that day, maintain the reputation of his countrymen. He repeatedly shot into the centre of the white, though the marks were erected at the extraordinary distance of twelve score yards apart. A simultaneous burst of admiration marked the delight and astonishment of the vast assembly who witnessed this fine display of skill and personal strength;” l

“Henry VIII. himself shot matches with his courtiers for what would now be considerable sums, and archery must in his reign have served as an opportunity for a very fair gamble. A few of the many entries relating to archery in his privy purse expenses are given, from which it will be seen that Anne Boleyn also patronized the sport:–” li

Not only was Henry an excellent shot he also made laws to encourage the practice of archery and established the charter for the Fraternity of Saint George in 1537 for the express purpose of shooting all types of missile weapons. The members of this company were nobles.

“THE ROYAL CHAETEE OF INCORPOEATION GBANTED TO THE HONOUEABLE AETILLEEY COMPANY BY HENEY VIII., 25th AUGUST, 1537, UNDEE THE TITLE OF THE FRATEENITY OE GUILD OF ST. GEOEGE.* A Grant to Henry th’Eight &c To all Judges, Justices, Maires, Sheriffs, Bailiffs, Constables and other or Officers Artillery. Ministres and Subgiettes, aswell wt in the liberties as w’out, thies our Lres heryng or seyng, Gretyng. We late you witt that of or grace especiall certein science and mere mocion we Have graunted and licenced, And by theis Pnts Doo graunte and licence for us & or heyres, asmoche as in us is, unto our trusty and welbiloved Srvants & Subgiettes Sr Cristofer Morres, Knight, Maister of or Ordenances, Anthony Knevett and Peter Mewtes, Gentlemen of or Preve Chambre, Overseers of the Fraternitie or Guylde of Saint George ; And that they and every of them shalbe Ovrseers of the Science of Artillary, that is to witt, for Longe Bowes, Crosbowes and Handgonnes, &c. whiche Sr Christofer Morres, Cornelis Jhonson, Anthony Antony and Henry Johnson that they and evry of them shall be Maisters and Eulers of the saide Science of Artillary, as afore is rehersed, for Long- bowes, Crosbowes and Handgonnes;” lii

Prince Arthur Tudor

Henry’s older brother Arthur was a noted archer.

“…, Prince Arthur Tudor, along with his companions, took to the activity with enthusiasm and shot “the game” regularly. The prince was well known for his enjoyment of shooting, and he proved to be an excellent archer; so competent was he, in fact, that it became customary to say of a good bowman that he “shot like Arthur”. In this regard he followed his father, Henry VII, who was no mean archer himself, and it was perhaps the king’s skill that fueled the enthusiasm of his two sons.” liii

Edward VI

Henry’s children, both Edward and Elizabeth, were also skilled archers. Roger Ascham, author of “Toxiphilus” was tutor to both of them

“In 1548 he was appointed reader to Princess Elizabeth, and probably the skill of Edward VI. and Queen Elizabeth with the bow was due to his instruction. Edward VI. seems to have been fond of archery, and from entries in his diary we find that he frequently saw his guards shoot, and himself contended with his courtiers; and he mentions that on one occasion M. le Mareschal St. Andre came to see him shoot, quite as if it was (which it may have been) a sight worth seeing.” liv

Elizabeth I

Queen Elizabeth learned archery at an early age and continued shooting into her late sixties.

“Queen Elizabeth was, according to the Veel MS. a good shot, as it says she ‘was so good an Archer that her side was not the weaker at the Butts,’ and she is also said to have organized a corps of archers among the ladies of her Court.” lv

“In the reign of Queen Elizabeth, a grand Archery meeting was held at York, which was graced by the presence of the principal nobility and gentry of the kingdom, though not of “the Virgin Queen.” This year [1582], there was a great shooting at York, by the Earls of Cumberland and Essex, whereat was two great ambassadors of Russia. Alderman Maltby (who was Lord Mayor of the city in the following year) was one of the choice Archers.” lvi

Reports of the time indicate that the Queen, until she was sixty-seven, hunted several times a week, sometimes shooting several deer with her crossbow.

Companies of liege Bowmen of the Queen

“After the destruction of the Spanish armada, fears being entertained lest the king of Spain should, out of revenge, send an emissary to attempt the life of queen Elizabeth, a number of noblemen of the court formed themselves into a bodyguard, for the protection of her person, and under the denomination of the “Companies of liege Bowmen of the Queen,” had many privileges conferred upon them. The earl of Leicester was captain of this company, which was distinguished by the splendour of its uniform and accoutrements.” lvii

It is interesting to note that this English company was reported to be armed with crossbows rather than longbows.

Conclusion

The above information is only a small sample of what exists supporting the idea that nobles frequently used archery for both the hunt and for sport. I was limited to what had either been written in or translated into English. There is even more to be found in other languages. Since I did not want the length of this article to become excessive, I have only included some of what I found.

There can be no question that hunting was one of the greatest interests, if not the greatest, of medieval nobility of all degrees. It served both a social and military training purpose. It even became with some, an overriding obsession. It is clear that due to their passion for hunting, that nobles of all degrees utilized archery from the early Middle Ages to the Renaissance. From the early years of Byzantium to the court of Elizabeth I, skill in archery was considered an important attribute of the nobility. Writers and religious leaders encouraged it as a requirement for the accomplished noble. Moreover, by the time of the Renaissance the idea of physical health and ability became part of the reason for its practice.

There is regular mention of the skills that were taught to the youth including archery as one of the basic and important abilities for noble youth as well as adults. In order to develop skill with the bow for the hunt, it was necessary to frequently practice. These practices are sometimes documented in the daily household accounts of kings indicating the amounts of money both received by the king for wining a match or the money paid out for his losing. There are also records of dukes winning crossbow major competitions.

There is no question that when the writings and images of the period are studied, that nobles of all degrees from kings and dukes down to knights and squires and even the clergy used archery for the hunt as well as for sport. The current research into medieval hunting also strongly supports this idea. The fact that noble women also took part in this activity, even to the point of open competitions with men, is notable. In a time of paternalistic dominance, women could and did achieve some equality with men by their ability with the bow and even exceeding men in levels of skill.

Archery guilds and fraternal organizations as well as royally chartered groups add to cross class fraternization and social mixing, thus continuing the social changes brought forward by the fall of the feudal system. In the face of this evidence, assertions that the bow or crossbow was merely a ‘peasant’ weapon are completely without foundation. The skill and the activity of archery, be it for hunting, sport, or military use, broke barriers between social groups, and even genders, for the love of the use of the bow and crossbow.

Endnotes

i Jim Bradbury, The Medieval Archer (New York: Saint Martin’s Press, 1985) 165.

ii Bradbury, 165.

iii Erik Roth, With a Bended Bow (Gloucestershire: Spellmount, 2014) 174.

iv Ryan R Judkins, “The Game of the Courtly Hunt: Chasing and Breaking Deer in Late Medieval English Literature” The Journal of English and Germanic Philology, 112.1, 2013) 70

v Bradbury, 169.

vi Roth. 28

vii Francis Turner Palgrave. The History of Normandy and of England, Volume 1 (London, Macmillan and Company, 1878) 180.

viii John Marshall Carter. “Sport, War, and the Three Orders of Feudal Society: 700-1300”, Military Affairs, Vol 49, No. 3, Jul.,1985. 137

ix Roth. 28

x Roth, 26

xi Richard Wadge. Archery in Medieval England: Who were the Bowmen of Crecy? . (San Fransico,The History Press, 2012) 32

xii Earle F Zeigler, Sport and Physical Education in the Middle Ages, (Bloomington, IN, Traford, 2006) 44.

xiii Wadge. 217.

xiv Joseph Strutt, and Co. 1903) Page 4.

xv Roth, 28.

xvi The King’s Mirror: Sports and Pastimes of the People of England. Book I, Rural Exercises Practiced by Persons of Rank. (London, Methuen Speculum Regalae, – Konu Larson, Laurence ngs Skuggsjá, Trans. Laurence Marcellus Larson, (Cambridge, Harvard University Press,1917) 213

xvii Kings Mirror, 219

xviii Ronald H Fritze & William Baxter Robinson, Historical Dictionary of Late Medieval England, 1272-1485, (Westport, Conn., Greenwood Publishing Group, 2002) 170.

xix David Nicolle. The Venetian Empire 1200-1670 (Oxford,Osprey Publishing, 1989) 7.

xx M. E Mallett and J.R. Hale, The Military Organization of a Renaissance State: Venice C.1400 to 1617, (Cambridge, Cambridge University Press, 2006) 403.

xxi John J Butt, Daily Life in the Age of Charlemagne, (Westport, Conn., Greenwood Publishing Group, 2002) 150.

xxii Richard Wadge, Arrowstorm: The World of the Archer in the Hundred Years War, (San Fransisco,The History Press, 2015) 84.

xxiii Joseph Strutt & William Hone, The sports and pastimes of the people of England: Including the rural and domestic recreations, May games, mummeries, shows, processions, pageants, and pompous spectacles, from the earliest period to the present time (London, William Reeves,1830) 17-18.

xxiv Earle F. Zeigler, Sport and Physical Education in the Middle Ages, (Victoria, BC, Traford, 2006) 18.

xxv Nicholas Orme, Medieval Children, (New Haven, CT, Yale University Press, 2003) 182.

xxvi Orme, 82.

xxvii Wadge, 84.

xxviii Wadge, 84.

xxix Wadge, 84.

xxx E. Hargrove. Anecdotes of Archery from the earliest ages to the year 1791 (York, Hargrove’s Library, 1845) 48

xxxi Roth, 212.

xxxii Richard Wadge, Archery in Medieval England: Who were the Bowmen of Crecy?, (San Fransico, The History Press, 2012.) 134.

xxxiii Wadge, 108

xxxiv Wadge, 108.

xxxv Wadge, 114.

xxxvi Wadge, 117.

xxxvii William Joseph Baker. Sports in the Western World. (Champaign, IL,University of Illinois Press, 1988) 60.

xxxviii William Harrison Woodward. Studies in Education During the Age of the Renaissance, 1400-1600, Volume 2 of Contributions to the history of education (Cambridge, University Press, 1924.) 291.

xxxix Baker, 59-60.

xl C.J. Longman and Col. H. Walrond, Archery (London, Longmans,Green, and Co. 1894) 164.

xli William Harrison Woodward, ed. “Aeneas Sylvius Piccolomini, Pope Pious II 1458 to 1464 De Librorum Educatione (1450)”, 10 June, 2016, http://history.hanover.edu/texts/aeneas.html page 2.

xlii Baker, 73.

xliii Laura Crombie, From War to Peace: Archery and Crossbow Guilds in Flanders c. 1300–1500, PhD dissertation (University of Glasgow, 2010) 112/65.

xliv Peter Arnade. Realms of Ritual. Burgundian Ceremony and Civic Life in late Medieval Ghent (Ithaca, NY, Cornell University Press, 1996) 71.

xlv Crombie, 118/68.

xlvi Hargrove, 48.

xlvii Longman, 163.

xlviii Anon. “Margaret Tudor Queen of Scotland Facts, Biography & Information”. 13 June, 2016 http://englishhistory.net/tudor/relative/maret-tudor/ .

xlix Anon. “Mary, Queen of Scots: Biography, Facts, Portraits &

Information”, 13 June, 2016 http://englishhistory.net/tudor/relative/mary-queen-of-scots/

l Hargrove, 54.

li Longman, 163.

lii George Alfred Raikes, editor. The Royal Charter of Incorporation Granted to the Honourable Artillery Company of Henry VIII., 25th August, 1537: Also the Royal Warrants Issued by Successive Sovereigns from 1632 to 1889, and Orders in Council Relating to the Government of the Company, from 1591 to 1634 (London, C.E. Roberts, 1889) 3.

liii Hugh David H Soar, The Romance of Archery: A Social History of the Longbow ( Yardly, PA, Westholme Books, 2008) 13.

liv Longman, 164.

lv Longman, 164.

lvi Hargrove, 58.

lvii Anon. The British Cyclopaedia of the Arts, Sciences, History, Geography, Literature, Natural History, and Biography .Volume 3 of The British Cyclopaedia of the Arts, Sciences, History, Geography, Literature, Natural History, and Biography (London, Wm. S. Orr and Company, 1838) 799. July 20, 2016